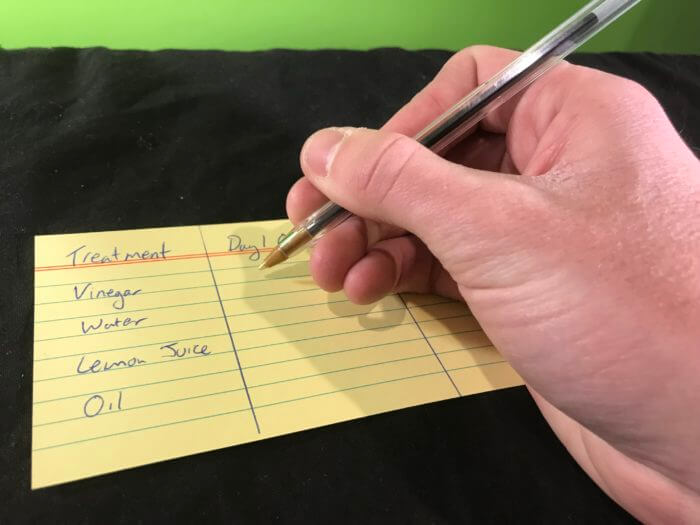

You Will Need:

- 6 Test tubes or plastic cups

- 6 Steel nails (avoid galvanised ones)

- Coke

- Water

- Lemon juice

- Vinegar

- Cooking oil.

- Optional: Saltwater, detergent.

- Adult supervision

Set up the 6 test tubes or cups as shown in the picture above. This experiment is very much about variable testing!

Take a photo and write down your observations of each nail at the start of the experiment. This is also a good time to enter this into your own classroom blog!

Optional: Weigh each nail with an accurate scale at the start and the end of the experiment.

Optional: Try different nails in the same liquid… do they rust differently?

This setup is just one way of running this classic rust experiment. You could also try the following experiment conditions too:

- nail completely submerged in water vs. half submerged.

- nail completely submerged in water with a layer of oil over the top of it.

- nail in salt water vs. nail in pure salt

School science visits since 2004!

– Curriculum-linked & award-winning incursions.

– Over 40 primary & high school programs to choose from.

– Designed by experienced educators.

– Over 2 million students reached.

– Face to face incursions & online programs available.

– Early learning centre visits too!

Why Does This Happen?

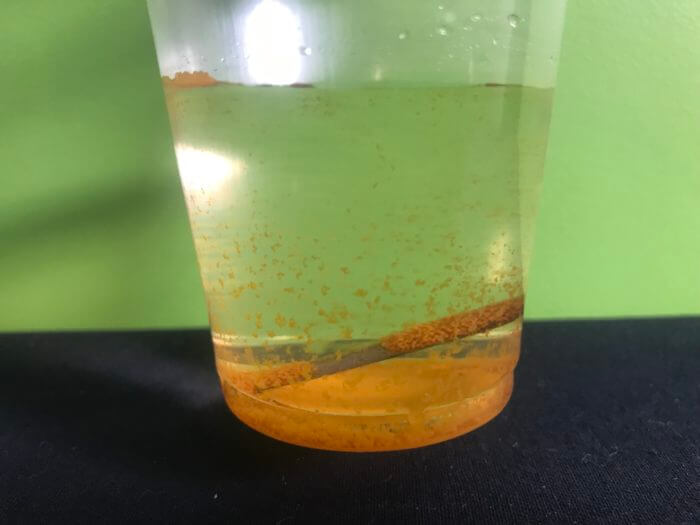

Rusting is the oxidation of metal, whereby the oxygen in the environment combines with the metal to form a new compound called a metal oxide. In the case of iron rusting, the new compound is called iron oxide… also known as rust!

This science experiment is all about controlling variables to explore which material will rust an iron nail first.

Variables to test

- Try boiling the water… does this make the nail rust faster, slower or is there no impact on the rusting time?

- What happens when you use different liquids?

- If you scratch the nail first, will it rust faster or slower?

- What if you use iron wool and iron filings instead?

- Try galvanised nails

Further information

Rusting, also known as corrosion, is the reddish-brown layer formed over an iron when exposed to air and water. Rusting occurs mainly because of a chemical reaction between iron with water and oxygen in the air.

Simple formula…

Water + Oxygen + Iron = Rusting

The chemical reaction usually occurs very slowly and it is an oxidation process. Rusting can also occur on other metals such as copper and they may not always be called ‘rust’.

Rusting can also occur in water. The carbon dioxide gas in the air mixes with water to form a weak acid called carbonic acid. This acidified water can dissolve some of the iron and water begins to break down into oxygen and hydrogen. The free oxygen reacts with the dissolved iron to form iron oxide or rust.

From colour changes to slimy science, we’ve got your kitchen chemistry covered!

Get in touch with FizzicsEd to find out how we can work with your class.

Chemistry Show

Years 3 to 6

Maximum 60 students

Science Show (NSW & VIC)

60 minutes

Online Class Available

STEM Full Day Accelerator - Primary

Designed from real classroom experiences, this modular day helps you create consistently effective science learning that directly address the new curriculum with easily accessible and cost-effective materials.

How many day will nail rust in tap water,vinegar,salt water, sprit and cooking oil

Hi Kolwawole!

Thanks for your question. The time to rust for the nail is highly dependent on the liquid the nail is immersed in. In water, you tend to see the beginnings of rust within a couple of days or so whereas other liquids take longer. Try the experiment out and let us know your results!

I bought non galvanised steel nails (they are called bright steel) and I have had them in my liquids (salt water and tap water) for a week now and instead of showing signs of rust they have just gone a grey colour. Do you know why? How can I adjust the experiment to make them actually rust? Thanks

Interesting! It looks like that if your nails were non-galvanised, it would have been to do with dissolved minerals such as carbonates in your water. The more carbonates, the ‘harder the water’. The harder the water the more difficult it is to rust a hot-dip galvanised nail as it affects the pH and the action of sodium and chlorine ions that come from the dissolved salt in the water (see this link). The thick layer of Chromium and Zinc on the galvanised steel slows the rusting as it prevents oxygen reaching the metal (at least for a while). You can actually see this affect by scratching off part of the galvanised layer and then letting this area rust as you’ve removed the protection (read up on crevice corrosion).

The thing is, your bright steel nails are non-galvanised. This means they should have little to no protection to the salt. If left for longer, the nails should begin to corrode on the outside. The rust formed on the outside is still permeable by the water and salt ions, which means that we would expect this rusting to happen underneath the top layer of rust as well. This should continue until the nail becomes completely iron oxide (rust). Let us know if this happens! For full details on the chemistry of nails rusting, check out csun.edu.

Thanks for your question!

I’m really confused about how can I weigh corrosion in metals. Can you please help.

Hi Rouzana! If you are able to have access to laboratory scales within a high school, you should be able to take a measurement of each nail mass before and after the experiment. The more sensitive the scales, the better!

hi can you please tell me the aim and the hypothesis of this experiment. thanks

Hi! Here’s something that could start you off;

– Aim; To determine which liquid produces the most rust on an iron nail.

– Null Hypothesis; There will be no change in rust on an iron nail when immersed in ‘ABC liquid’.

Have fun!

Hi!

Do you know what type of reaction this and also the science behind it?

Thank you!

Hi Lara!

This is an example of a Redox reaction, wherein this case the iron reacts with water and oxygen to form hydrated iron(III) oxide, which we see as rust. See further details here!

I wanted to do a variation of this experiment for my high school class. Instead of weighing the change in mass to determine the amount of oxidation, I was wondering if there was a chemical that could dissolve only the nail(iron or any other metal) leaving the remaining iron oxide behind.

Sorry Michelle, I’m not sure of a chemical that will do this. If you find out please let us know!

hey

can you tell us the chemical formula of the equation iron+water+oxygen= hydrated iron(III) oxide

Should we cover the bottle of water to hasten the rusting process ?

thank you

Hi Viv!

There’s actually a few things going on here over three separate reactions:

A great summary of the three reactions can be found here

The final balanced equation is below, however this covers both Fe(II) and Fe (III) ions.

4Fe + 3O2 + 6H2O → 4Fe(OH)3

If I have four solutions (water, salty, bleach and with oil) which will corrode the fastest? the slowest?

Hi!, I placed screws/nails in vinegar and lemon juice and after 9 days they turned black, I was wondering what is the cause of this?

Hi! The acid from both liquids removed the outer coating and exposed the underlying metal to the air which caused oxidation

hi,

I have a doubt, I used the ss steel screw ( nail) and I kept them in vinegar, cooking oil & lemon juice. But when I checked it in the next day the screw in the vinegar turned silver to black. The same happened the same but it happened to the lemon juice

Hi! Both the vinegar & lemon juice are acids that removed the coating and allowed the underneath to oxidise.

What is their rate of corrosion (Reaction)? thank you

Hi! This is dependent on the concentration of the acids and the temperature

what are the factors that affect/speeds-up corrosion?

Solution concentration & type as well as temperature. Isolate a variable and see which make the greatest effect!

what liquid makes nails/screws rust the fastest?

Hi Piper! Please try the experiment to find out and let us know!

Do you know what are the independent, dependant and controlled variables in the experiment.

Hi! Please have a read of this article to help you with this answer 🙂

https://www.fizzicseducation.com.au/articles/variables-teaching-the-heart-of-science-experiments/?recaptcha_response=